It’s time for us, as a polis, to revisit the mechanisms that distinguish politics, investing, and charity, the values we ascribe to each, and the boundaries that define them.1

Lucy Bernholz, self-described “philanthropy wonk,”2 wrote this in a short piece about the initial way the press covered the announcement of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan announced the Initiative on December 1 last year in a letter to their newborn daughter, Max.3 In the letter, they pledged to give to this Initiative 99% of their Facebook shares over their lifetime, currently estimated to be worth $45 billion. The mission of the initiative, they said, is “to advance human potential and promote equality for all children in the next generation.” Their initial areas of focus, they said, “will be personalized learning, curing disease, connecting people, and building strong communities.”

The big news – in the philanthropic world, at least – is that the initiative will not be a charity despite its stated intention to do good in the world. It will be a limited liability corporation, or LLC. The Initiative’s Facebook page said, “The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s configuration gives it the freedom and funding to take big swings at the causes of humanity’s troubles.”

On Facebook, Zuckerberg discussed the decision to use an LLC: “This enables us to pursue our mission by funding nonprofit organizations, making private investments, and participating in policy debates.” He also stressed that, since the new venture is an LLC, putting their money there does not give them any tax benefits.

At the same time, a piece by Suzanne Wooley on BloombergBusiness makes some of the benefits of an LLC clear and suggests ways that the LLC form determines what the Initiative can do.4 1) There won’t be limits on advocacy and lobbying. 2) The Initiative can turn a profit, though that’s not the aim, Zuckerberg says. 3) It will be easier to do joint ventures with for-profit companies. And 4) it avoids the requirement, placed on a nonprofit foundation, that at least 5% of its value be given away each year. In addition, Zuckerberg is CEO of the new Initiative, meaning, as Kurt Wagner put it on <RE/CODE>, “…Zuckerberg can spend his billions wherever he wants.”5

And, now, I come round again to the quote from Lucy Bernholz that I started with. Right after the quote I used, she goes on to say:

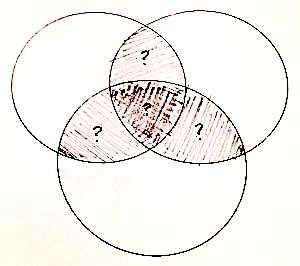

Using all three tools [charity, investing, and politics] may be strategically advantageous to donors. But democracies may have good reason to not allow these activities to become interchangeable even as they may be complementary. If we believe there are differences between political activity and charitable giving – for example, if we think one should be transparent and the other has room for anonymity – we need to protect those distinctions.

The blurring of lines between charity, politics, and investing can have some upsides, but the results brought about by those who’ve been doing it for a long time should give us pause. It’s the systems and rules about these activities that need fixing. And that’s up to us.

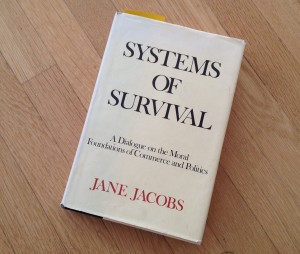

In addition to suggesting that we understand the distinctions between the mechanisms of and the boundaries defining these three worlds, Lucy asks us to consider the “values we ascribe to each.” Thinking especially about how the three realms differ from each other in terms of their values calls to mind a framework I’ve carried with me since the mid-1990s. It’s one I adopted from Jane Jacobs in Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics, published in 1992.6

In this book, Jacobs first identifies two different ways of getting a living, that is, of ways to survive – trading and guardianship. She calls them “syndromes.” Trading includes the whole commercial, profitmaking world of people who trade or produce for trade. Guardians, on the other hand, traditionally were hunter-gatherers, raiders, and warriors who survived by taking (also meaning, as I understand it, by taxing). Today, guardians are also involved in protecting territory and resources, not just taking them. Among others, the state in its various forms, governmental agencies, legislatures, the police, and many religious organizations are guardians.

In her book, Jacobs contends that each of the syndromes has its own set of morals – manners, customs, mores, and social sanctions that provide systems of informal social regulation. The morals in the commercial syndrome include, among others: be honest, respect contracts, compete, come to voluntary agreements, shun force, use initiative and enterprise, be efficient, promote comfort, collaborate easily with strangers, be thrifty, be optimistic. The guardian syndrome, on the other hand, includes morals such as: shun trading, exert prowess, be obedient and disciplined, adhere to tradition, be loyal, respect hierarchy, show fortitude, take vengeance, make rich use of leisure, be fatalistic, treasure honor.

What really grabbed my attention was that, as Jacobs presented them, the two sets are not interchangeable. Qualities found in one syndrome are not appropriate in the other. Beyond simply their differences, she believed that the two syndromes, while interdependent, must function separately. In fact, she said, “Crazy things happen systematically when either moral syndrome…embraces functions inappropriate to it.” This can lead to “systemic corruption” and to what she called, “monstrous hybrids.”

In notes to myself at the time, I wrote, “The idea that different moral standards apply in different circumstances is powerful. We live, it seems, with an underlying assumption that a single moral standard should apply throughout. It would be so much cleaner and easier that way. But the argument for different moral syndromes rings true.” However, I immediately went on to tell myself, “I’m convinced that two are not enough. Gifts and gift exchange are missing.” After making lists of morals for all three, I wrote, “My guess is that gifts and voluntary efforts may be an invisible but essential partner of trading, and maybe taking, too – both need gifts, just as trading needs guardians and vice versa.”

So many more thoughts race through my mind as I write, but for now, I’ll just go back to Lucy’s call that we revisit the mechanisms that distinguish politics (the guardian), investing (the trader), and charity (the gift giver) and that we consider the values we ascribe to each and the boundaries that define them.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

Notes

- Lucy Bernholz, “What if the headline had read . . . ,” Medium, January 12, 2016.

- Digital Civil Society Lab: People, “Lucy Bernholz.”

- Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg, “A Letter to Our Daughter,” December 1, 2015.

- Suzanne Wooley, “Four Reasons the Facebook Fortune Is Going Into an LLC” BloombergBusiness, December 2, 2016.

- Kurt Wagner, “Mark Zuckerberg Responds to Critics, Explains Where His Money Is Going,” <RE/CODE>, December 3, 2015.

- Jane Jacobs, Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics, Random House, 1992.

![]()