Oh so thankful

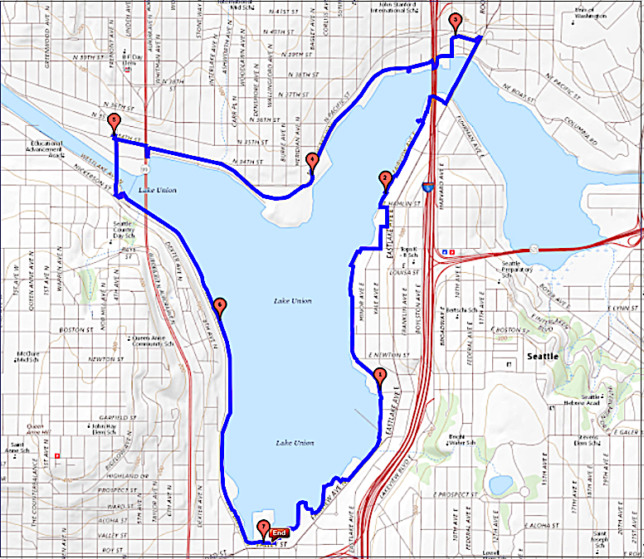

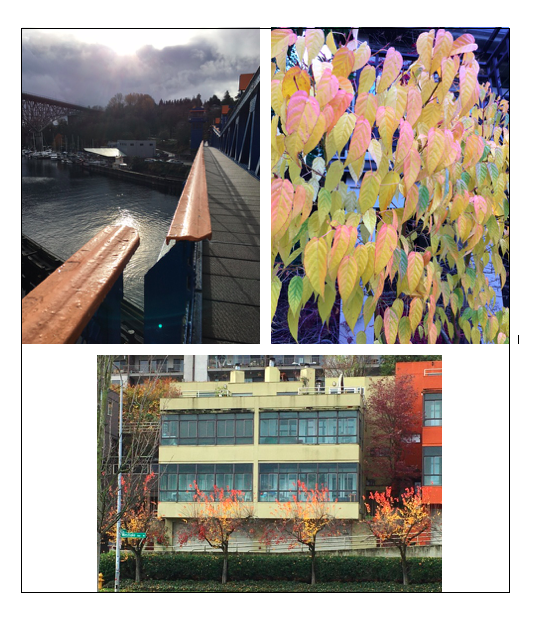

We walked alone together on Thanksgiving Day around Seattle’s Lake Union in an annual community walk dedicated to the last two of the Duwamish people to live on their traditional tribal lands near Lake Union—Cheshiahud and his wife Tleebuleetsa. For our pandemic times I adapted this tradition by encouraging friends to walk solo or in small groups and by inviting friends from around the country to join in. At least seventy-eight people helped make this a grand, dispersed-unity, Thanksgiving Mask-arade. It felt like a huge cross-lake, cross-city, cross-country hug.

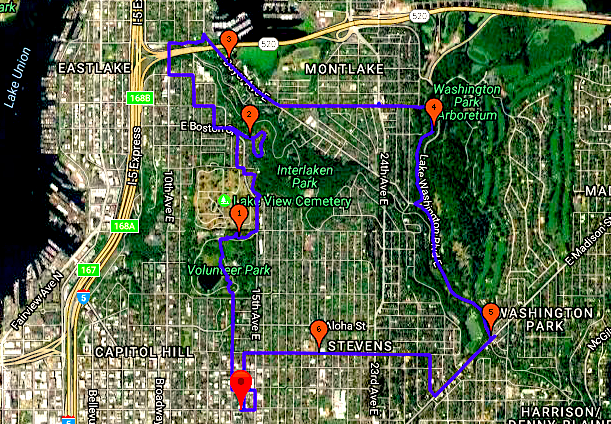

Email notes and photos indicate that at least twenty-eight of us walked along or around Lake Union, and at least sixty-nine others walked somewhere else: in the city (Queen Anne Hill, First Hill, Capitol Hill, Green Lake), in Washington State (Tacoma, Chuckanut, Port Townsend), or in places across the country (New York, North Carolina, Minnesota, California, and more). Altogether and nearly one hundred strong, we walked with eight dogs and two babes in strollers. We used walking sticks and a scooter. We walked through trees, over bridges, up stairs, along lakes and rivers, over hills, through an historic fort, along a sunny beach, and in the snow. We passed goats, people in funny hats, amazing fungi, a slug, one Christmas yard display, and a rainbow over Lake Washington. We walked in the daytime, at night, and at dusk with a full moon. A few of us even ran into each other, spotted by our bright yellow or orange attire.

![]()

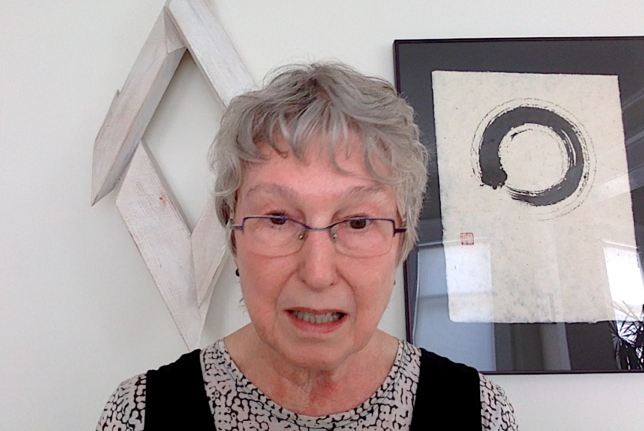

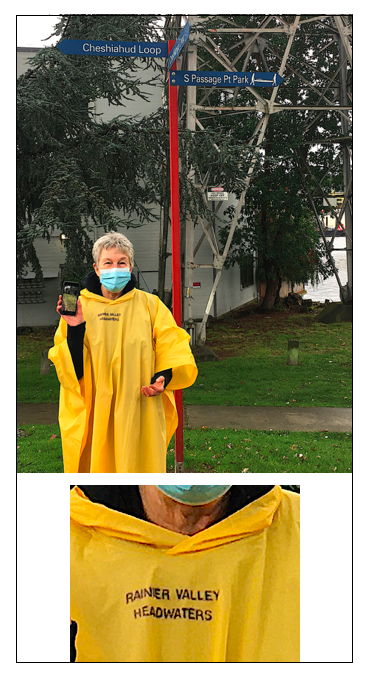

My long-time friend, Norie Sato, made the circuit around Lake Union with me. Norie was the first person to accompany me on my annual Thanksgiving walk around the lake after I’d been doing it solo for a few years. During that walk she also gave me the news that the City of Seattle had recently designated a path around the lake as the Cheshiahud Loop Trail. Directional signs began to show up shortly after that. The walk with her that day inspired my invitation to other friends to join in what, since 2010, has been an annual tradition. Below is Norie at the entrance to Good Turn Park on the northeast side of the lake. It’s one of many street-end parks created by the City all around the lake. It’s a regular stopping point on our annual walk. And below that you’ll see Norie standing with the Dunn Lumber mural at the north end of the lake near Gasworks Park where we started.

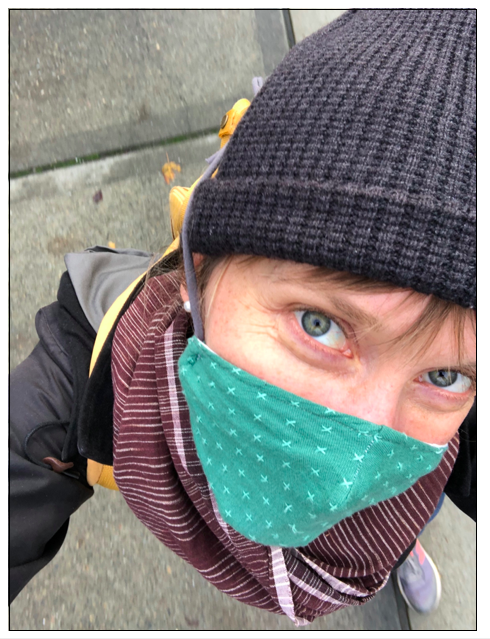

Next I offer proof that we were, indeed, on the Cheshiahud Loop Trail. I’m wearing a yellow rain slicker that had been folded up with my winter things, not worn for years, proof of my pack-rat leanings. As I unfolded it this year I discovered it came from a much-loved site-based artwork by artist Susan MacLeod sponsored by and/or in the late 1970s on the sports field at Seattle University. The memories added to my gratitude for the day.

Following are photographs and notes I received from walkers after they finished walking. First are the Lake Union walkers. Their photos are evidence of Lake Union’s history as a working waterfront, long established as such in the city’s zoning code. After that are the friends who walked in their own neighborhoods or other favorite places around the city, state, and country. Altogether, we covered a lot of territory!

LAKE UNION MASK-ARADE WALKERS

“A tale of 4 bridges…The only orange thing I have is a cotton scarf that I got during Bear Training Level I for Seasonal Employees, while I was artist in residence in Glacier National Park… and indeed, we saw no grizzly bears walking around Lake Union : – ) – nor anyone else in orange : – ( ”

— Suze Woolf & Steve Price, champs who not only walked the entire route, but created an excellent visual story of it all.

![]()

“Missed you but we did it (well, part of it…) Here we are at our starting and finishing place, MOHAI parking lot.”

— Paul Taub & Susan Peterson

![]()

“Here’s a couple of photos. We really enjoyed the walk! We stopped at Good Turn Park so we could get home to make a Thanksgiving dinner. I designed Good Turn Park in the 90’s. But it has fallen into disrepair and weeds. The Parks Dept. refuses to maintain it because it’s on SDOT property.Neighbors tried maintaining it for years but they lost their leader about ten years ago. The crazy bench seat I was on is down by the beach at Good Turn at the foot of the big redwood that someone planted when the park was new. The ceramic tiled bench was near Pete’s store.

“We met Paul de Barros and Sue Dickson along the way. Very nice little chat. Paul and Sue forgot about wearing yellow or orange. Piper and I made up for them!”

— Tom Zachary & Piper Greenwood, Seattle

![]()

A number of people ran into each other and sent me criss-crossing photos. Their comments and photos follow.

“Happy Thanksgiving, Anne. Well, I thought I could catch you and Norie before finishing my lap but then I ran into Piper and Tom, and we talked for a bit. I sure noticed every orange and yellow accessory along the way, this year!”

— Catharina Manchanda

“Happily saw Chiyo, Mark, and Catharina toward the end of my walk! Thank you for the inspiration, Anne. It’s a walk I’m going to take more often than Thanksgiving. I hope your walk was a fine one.”

— Barbara Johns, who sent more photos in a second message which appear as the last entry from Lake Union Walkers.

“We enjoyed our first Thanksgiving walk with you. Here are some favorite moments.”

— Chiyo Ishikawa & Mark Calderon

“I was so grateful to find this unlocked port-a-potty at just the right time!”

— Mark Calderon

![]()

The first Mask-arade person Norie and I saw on our circumambulation of the lake was Debra Ross, seen here at Good Turn Park. It was great to see her.

![]()

Six close friends walked the lake together: Liz Brown, Suzy Schneider, Ellen Sollod, and Gene & Bill McMahon and their daughter Becky. Comments and photos follow.

“Here [the first photo below] is where we had to turn around…new construction and repairs predominant in this.”

— Ellen Sollod

“More beautiful trees at Green Lake but all in all a visually stimulating walk. I’m always on the lookout for trees but still have not identified that unusual one [final photo in the group]. Thank you Anne for your grand plan…we did eventually encounter more of your fellow walkers! Sorry we missed you and Norie! Enjoy your Thanksgiving dinners tonight!”

— Gene McMahon

![]()

“Rowan and I are going to Spokane for Thxgiving this year, so I did my Lake Union walk over the weekend [11/21/20]. Photo with yellow backpack strap attached. 🙂 ”

— Bonnie Swift

![]()

“On my way I remembered about the yellow. So first I found a scrap of old construction tape and tied that in my jacket. Later I added a yellow leaf. But I didn’t see any yellow in people except one guy in a bike who was wearing a yellow vest. I walked a little more than half the distance. This was a lot of fun thank you. I hope you’ll buy my novel The Aftermath from Amazon or Adelaide if you want an ebook!”

— Lyn Coffin

![]()

“This is just a short little note of thanks. This walk was the perfect holiday activity for my family; my mom, stepfather, two dogs and I walked the lake last Thursday in place of gathering for dinner. We so loved being outside encountering many familiar and friendly faces along the route. Thank you for organizing this and finding a creative and spirited way to make it happen, even during a pandemic. Yours fondly.”

— Sarah Traver, Seattle

![]()

“Thanks for the ‘MASK-querade’ walk. Sorry we didn’t run into you. We did the whole durn thing, clockwise from the MOHAI lot. We did hear from Tom and Piper along the way that you were up ahead but I guess you finished before we did. Man, my feet hurt when i got home!”

— Paul de Barros & Sue Dickson (photo by Tom Zachary & Piper Greenwood)

![]()

“Thank you so much for encouraging the walk. We did a semi loop this year. We saw Chiyo and Mark along the trail. Recognized more by their yellow and orange. Great idea because masks obscure everyone. So many joggers in black out.

“Love to you on this day and remembering the Duwamish peoples past and present.”

— Saya Moriyasu & Jeff McGrath, Seattle

![]()

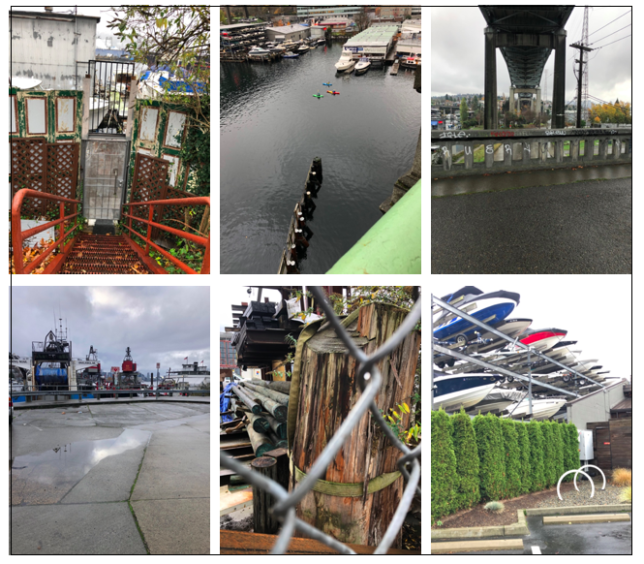

“I made a short visual journal, shortened further here, to send my Midwest siblings in advance of Thanksgiving day calls and remembering the Seattle get-together we missed last summer. Familiar sites to all who’ve made the walk, this one ending with my meeting friends. For your viewing pleasure! ”

— Barbara Johns, from her second message. Her photo journey around the lake is a nice complement to the one Suze and Steve offered at the start.

![]()

MASK-ARADE WALKERS FROM NEAR & FAR

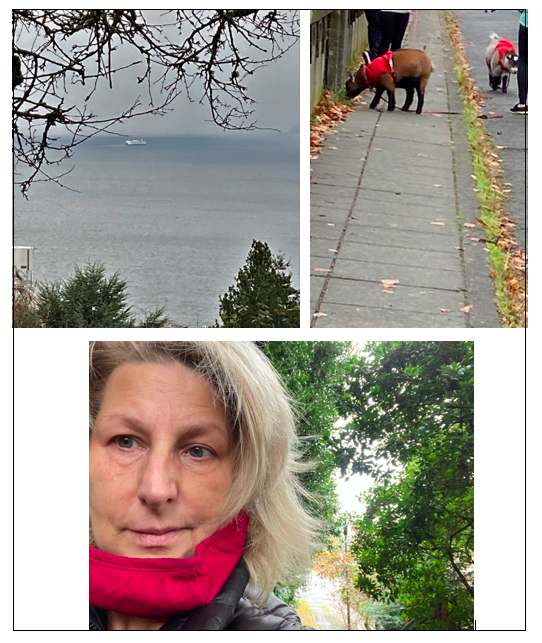

“Picture from my remote walking – Elliott Bay and Goats walking!”

— Edie Adams, Queen Anne Hill, Seattle

![]()

“Happy Ongoing Thanksgiving, Anne. I did not walk on Thanksgiving because it poured drenching rain here all day long. Instead Arty, pictured below in his puppy-cave, and I spent the day in our cozy house with great company on zoom. My dinner wore the day’s colors. And nature provided her own the next day for a walk in Dartmouth, the town next door to New Bedford, on a new property owned by the land conservation and walking trail provider, Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust.

“I trust you are receiving many of these delayed transmittals of Thanksgiving 2020. It was wonderful to read yours and remember the circumnavigations I’ve joined you for in past years. It is sweet to think of your emissaries all over taking the Cheshiahud Loop to other parts of the world, as well as to imagine joining you again to trek the original around Lake Union some year soon.”

— Rebecca Barnes with friends, New Bedford, Massachusetts

![]()

“Three photos from my Thanksgiving walk today, Anne. Not at Lake Union unfortunately, but still sweet. I hope you had an excellent walk with Norie.”

— John Boylan, Seattle

![]()

“Seattle U, between dinner and pumpkin pie. The Ent.”

— Jan and Doug Bradley, First Hill, Seattle

![]()

“I probably missed the deadline but I wanted you to know that I joined you in spirit on Thanksgiving as I walked to a park in Shoreline honoring the Duwamish peoples.”

— Brian Branagan, Shoreline

![]()

“Long Island City with Manhattan in view over East River w Andru, Howard, James, Ray & Wendy 11/26/20. It gets dark early lately! ”

Sent a day or so later, but still in response to the Mask-arade posts:

“oops meant to send! thanks for letting us be unity too — we were in the park where Bernie & AOC spoke in 2019 -– it was so fab, 25K people & love fest.

“just went to our little park, 3 bands playing at once with the ping pong table, hearing it all, golden gingkoes and cheerful people – very sweet. first time to play pingpong & go to a zoom meeting at the same time…only one dog stole our ball briefly”

— Wendy Brawer, Ray Sage, and friends, Brooklyn, New York

![]()

“Here’s our photo from our walk! We kept it socially-distanced and it was just me and my pup, P! We walked around Highland Park in LA today, about 4 miles 🙂 ”

— Jess Capó, Los Angeles

![]()

“Love the notion of a collective meander of grace and gratefulness. Here is the view of my late late walk along the shore of Crown Harbor off of Alameda Island, CA.”

— Bill Cleveland

![]()

“This is woody, michael, jeanne, Louca and me at green lake starting at 11am today. Thanks for the inspiration! The folks in funny hats were along the route – a friendly flock!Happy thanksgiving 🐿 ”

— Rebecca Cummins with Woody Sullivan and Michael Swain & Jeanne Foss with their son Louca, Green Lake, Seattle

![]()

“Lake Union” walk…Well I’m afraid to say we cheated a bit. We were just about to leave the house and go out to Lake Union, when it started to pour, so we waited – and then realized that there was no way we could do the full loop and get the food in the oven in time. So we instead did a walk on Capitol Hill. But we did think of you and we did wear yellow jackets. Happy Thanksgiving!”

— Richard Farr and Kerry Fitz-Gerald, Capitol Hill, Seattle

![]()

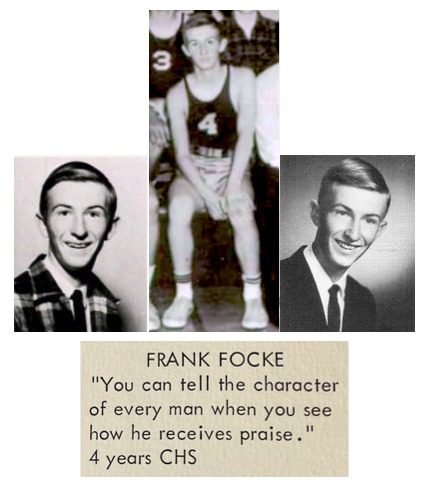

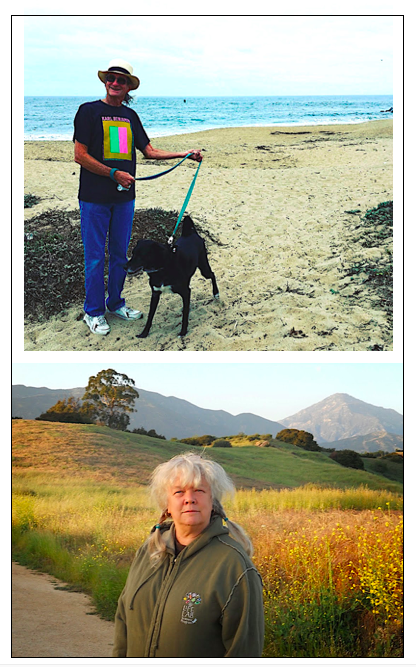

Here are a couple of photos from Ross Focke & Beth Benjamin: Beth at Beth Johnson’s pastures and Ross & Luke on the beach.

— Ross Focke, Beth Benjamin, and their dog Luke, Claremont, California

![]()

“We have had a fun weekend and with cherishing the time with Heather and Eric, have not had a chance to sit down and send this off. Confession, we took our walk on Friday. Mark and I were pretty busy on Thursday getting everything ready.

I am thankful for being able to share Thanksgiving weekend with my favorites, Mark, Heather and Eric. I am also thankful that the magical Fort Worden, where this photo was taken, is practically in our backyard. And thankful that I can share and be a part of this community, looking forward to seeing the photos on the website. Hope you had a wonderful walk on Thanksgiving!”

— Kathy Fridstein, Mark Manley, Heather Manley, Eric Manley, Port Townsend, Washington

![]()

“We will walk a bit outside of La Conner with your walk in mind.”

— Cathy Hillenbrand & Joseph Hudson, Seattle (La Conner is a small town in Skagit County, Washington)

![]()

“Weisbecker/Law/Louie/Matumona Family masked walk

Our walk to Sunset View Park today.

Strange crew.”

— Carolyn Law & Andy Weisbecker, Beth Louie & Jake Weisbecker with their daughter Bellamy Gabriella Weisbecker, Hélène Matumona & Lucas Weisbecker with their son Loreto Jabulani Weisbecker, Greenwood/Sunset View Park, Seattle. This family definitely gets the prize for the largest family to participate in the 2020 Mask-arade!

![]()

“Hope you’re having a great day. Here we are scooting on Lake Washington.”

— Margie and Brian Livingston, Lake Washington, Seattle

![]()

“Here we are on our Thanksgiving walk in St Paul about to head up the steps in the background!”

— Sarah Lutman & Rob Rudolph, Saint Paul, Minnesota

![]()

“1 Out our front window a few days before Thanksgiving…….now all melted.

2 Me back home wearing my “Anne Focke Walk” yellow.

Nice to talk with you.

Stay healthy.”

— Peter Mahler, Madison, Wisconsin, who, in a first for a Thanksgiving Lake Union walk, engaged me in a Facetime call while I walked over the University Bridge.

![]()

“Anne, Happy Thanksgiving to you! Tom and I always take a walk on Thanksgiving and today turned out to be a very pretty day… we see the Linville Gorge on the front end of our walk and the Black Mountains in the distance midway through the walk. Your lake walk with friends is a great idea…we are celebrating all we have to be thankful for with you today.”

And a little later:

“I didn’t tell you where we are or what we are thankful for…and we aren’t wearing masks because we are the only ones on this property…We started our walk at home with the Linville Gorge behind us along with farms beside the Blue Ridge Parkway and midway through a neighboring farm we have the Black Mountains behind us. We have so much to be thankful for…valuable friendships, good health, creative lives, precious freedoms, and an incoming commitment to addressing social justice inequities.”

— Jean McLaughlin & Tom Spleth, Little Switzerland, North Carolina

![]()

“Good Morning Anne!

“I trust your Mask-a-raid went off like clockwork. We took an early morning hike in Moran State Park! Looking forward to seeing your photo compilation. ”

— Heather & Greg Oaksen with their son, Eric Oaksen, Orcas Island, Washington

![]()

“This is so beautiful, Anne. I’d meant to send pictures earlier. I didn’t find anything yellow to wear (though I chose an orange hat and carried the gingko leaf from our yard to the coast, in tribute to you) but Nathan, Zoe and I did go for a walk on the Santa Monica beach.”

— Claire Peeps with Nathan Birnbaum and their daughter, Zoe, Santa Monica, California

![]()

“Happy Thanksgiving +1, Anne. Glad the physically distanced Maskarade went well and you and Norie had fun. Thanks for the invite. Carrie and I and the girls did get out to walk in the hills above Chuckanut Drive. Cheers to you through all pandemic challenges.

P.S. Took the masks off for the pic…”

— Simon & Carrie Pritikin with their daughters Jasmin and Olivia, whose home is in Seattle

![]()

“I wish we took pictures to share – we did the Ruston Parkway in Tacoma. Hope you are doing well and having a nice quiet holiday season.”

— Dechie Rapaport with Willie and Gabby, long-time Thanksgiving Lake Union walkers, Tacoma, Washington

![]()

“Walked with son, who is now back on The Big Island, on Thanksgiving Day. Walk is along La Jolla waterfront where sea lions love to loll on the beach. I 🤗”

— Yvonne Sanchez, who lives in Seattle but was visiting family in San Diego

![]()

“Hope you had a great walk today. Thinking of you from afar as we walked at Kobayashi Park in University Place (next to Tacoma and my new home….Seattle got too expensive). It’s a short walk through the woods and beautiful stream. My guy in the picture is Richard Reynolds.

“Now, on to the last of cooking and finally eating.

“Till we meet in real life again!🧡🍁🧡 ”

— June Sekiguchi and Richard Reynolds, Tacoma, Washington

![]()

“Thanksgiving Walk 2020: Aaron, Connor & I walked around the reservoir at Horizon View Park in our town: Lake Forest Park. Didn’t take pics and forgot to post a note, but your walk inspired us, so that’s what we did as part of the Dispersed Unity Mask-arade!!!!”

— Anne Stadler with Aaron Stadler and Connor Fosse Stadler, Lake Forest Park, Washington

![]()

“Happy Thanksgiving from Philadelphia! I spent most of the day tucked in at home with my husband and our 10-month-old daughter, but was able to sneak out shortly before sunset for a walk around the neighborhood while the turkey was cooking. Never underestimate the power of a walk, no matter how short! We live in Fishtown, a neighborhood just northeast of Center City and close to the Delaware River – and also close to a historic cemetery with beautiful old Sycamores. This is where I went on this little stroll. Here are a couple of images of the moon rising over its trees, as well as the view leaving our building (the globe light fixtures also reminded me of the moon). I would love to do the route around Lake Union someday… I’ve done a yearly Good Friday walk since 2014, one year circumnavigating Manhattan Island, which feels like the opposite in terms of looking out to the water as a constant versus the Lake Union route looking in. Either way, there’s a pull in that space where water meets land, and discovering all of the inlets and hidden gems.”

— Erin Sweeny, Philadelphia

![]()

“Greetings from Rainier Beach, Anne, I joined my family and we walked by Lake Washington, around Genesee. The highlight was seeing this Rainbow!

“On to Hanukkah, the Solstice, Christmas, New Years, and more.”

— Diane Tepfer and family, Rainier Beach, Washington

![]()

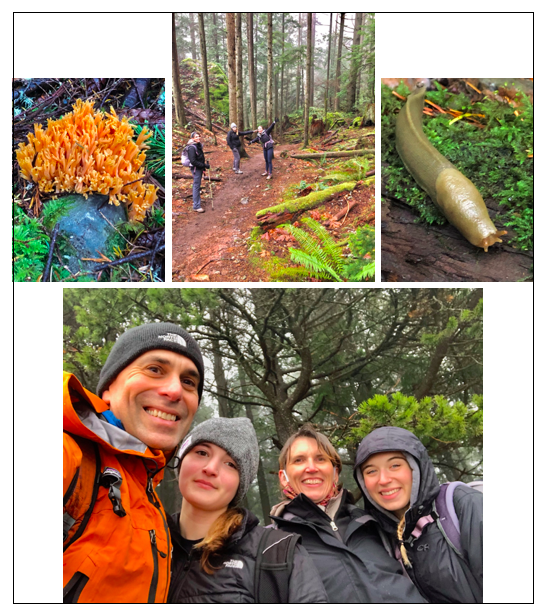

“Thankful for the wild fungi on parade in a forest near Tacoma on Thanksgiving!

Richard, the Wild Fungi (Fun Guy) in the South Sound”

— Richard Woo, Tacoma

![]()

A thousand and one thank-you’s to everyone who walked with us this year! It means so much to hear from all of you. You fill me with hope and thankfulness.

![]()

A final image from the east side of the Cheshiahud Loop Trail near the Eastlake Community Garden, a miniature Thanksgiving gathering, hosted by the two turkeys on the porch of the little cottage. They all seemed to be having a good time, and I doubt they dined on a “traditional” Thanksgiving meal.

![]()

![]()