Thinking about how we think about work matters

“Are you retired?”

In answering the friendly barista facing me with a smile, I stumbled a bit to find the best way to answer. You’d think, being well past traditional retirement age, I’d have a ready answer to such a straightforward question. My hesitation, though, had little to do with my age – I’m happy to be 71, lucky to be healthy in body and spirit, and always ready to acknowledge how old I am. The challenge was the meaning of the word “retire” and the assumptions it makes about work and jobs.

Am I working now? Well . . . “yes and no” or “on and off” or “it depends.”

Yes, I still need to make money beyond what I get from social security and modest savings. But even if I didn’t have to, I’m not sure I’d want to stop working, at least not as long as I can define “work” in the large, loose, multi-faceted way I’ve defined it over the years. Lines that might help me define my work have always been fuzzy – lines between my work and my social life, between work that pays my bills and work that I’m driven to do, lines between when I’m working and when I’m having fun.

The meaning of “work” as I’ve experienced it in my life doesn’t fit the conventions for it that typically surround us. In general usage the word is most often restricted to effort where money changes hands, and for many too many people that work is nasty and unsatisfying, especially if they’re at the bottom of the pay scale. But a whole world of real work is left out when it’s defined this way.

travail

trabajo

arbeit

John Budd, a university professor who studies and teaches about work, employment, and labor1, claims that the way we define work, the way we think about it, is deeply important to how work is structured in practice. A short piece on his blog “Whither Work?” considers the roots of our words for work and described the long history of negative associations with these words in our language.2 “Words indicating labor in most European languages,” he wrote, “originate in an imagery of compulsion, torment, affliction, and persecution.” The French word travail and Spanish trabajo are derived from the Latin, trepaliare, to torture, to inflict suffering or agony. “The German arbeit suggests effort, hardship, and suffering; it is cognate with the Slavonic rabota (from which English derives “robot”), a word meaning corvée, that is, forced or serf labor.”

oeuvre

opus

werg

But the meanings aren’t always negative. “While travail is rooted in torture, another French word for work, oeuvre, comes from the Latin opus relating to accomplishment and creativity. The word work itself is rooted in the ancient Indo-European word werg meaning, simply, “to do.” Budd concludes that words for work can be negative (to torture), neutral (to do), or positive (a work of art).

I was introduced to Budd’s ideas about work a few months ago at the first Chat Room, a quarterly forum on art in the age of the internet.3 Subtitled, “Value and Labor,” this event also posed a more specific question: “What are the trade-offs for artists, creative freelance workers, and other independent contractors in an economy altered by the internet?” As an introduction to these more specific questions, Minh Nguyen, the forum organizer, began by presenting John Budd’s “ten key conceptions of work.” Many other strands of the evening’s discussion were also fascinating, but the range of his ideas definitely got my attention.

a curse

freedom

a commodity

identity

service

In his 2011 book, The Thought of Work,4 Budd elaborates on these ten views of work and in the process explodes the narrow definitions we commonly use, narrow definitions that reduce work “to a curse or to a commodified, instrumental activity that supports consumption.” Being a fan of lists, I include his list of ten ideas.

A curse. An unquestioned burden necessary for human survival or maintenance of the social order.

Freedom. A source of independence from the dictates of the natural world, a way to express creativity and build culture.

A commodity. An abstract quantity of productive effort that has tradable economic value.

Occupational citizenship. An activity pursued by human community members entitled to certain rights.

Disutility. A lousy activity tolerated to obtain goods and services that provide pleasure.

Personal fulfillment. Physical and psychological well-being that provides more than extrinsic, monetary rewards.

A social relation. Human interaction embedded in social norms, institutions, and power structure.

Caring for others. The physical, cognitive, and emotional effort required to attend to and maintain others.

Identity. A method for understanding who you are and where you stand in the social structure.

Service. The devotion of effort to others, such as God, household, community, or country.

a job

work

as commerce

as a calling

Budd differentiated kinds of work in a much more fine-toothed way than I did in “Unpaid, in Spite of Their Value.”5 I made one main distinction, and it was bigger and more diffuse than any of his. Having learned from artists, I distinguished between a “job” and “work,” between work as commerce and work for the common good, between jobs that pay the bills and work that could be called a calling. And by calling, I mean work we’re compelled to do by something other than money – writing poems, composing songs, and making photographs, or teaching, neighborhood clean-ups, and caring for children. I’m grateful for the reinforcement I get from Budd’s multiple views.

Beyond simply identifying the various root definitions of work and his ten conceptions of it, Budd strongly believes that the way we think about work matters. “This should be more than an esoteric, intellectual exercise.” Our unstated views of work affect public policies and laws. When the unpaid work of artists, parents, and neighborhood volunteers is not viewed as “real work,” policies around compensation and benefits, for instance, don’t include them, and without money changing hands, the work and often the person doing it are less valued than wage-earners, not only by the world at large but too often by the people themselves. Budd writes:

“The linguistic features of work reflect the realities of human work… As a society, we need to re-connect with the deep meanings of work not only for individuals but also for democracy. We need to develop new norms that value work that is not rewarded by the labor market and create institutions for improving how work is experienced.”

I’ve thought about multiple meanings of work as I’ve gone from one sort of work to another, and I’ve done so right through my 60s without much of a pause at “mile marker 65.” While I’m sure our specific understandings of what we mean by work will keep changing, I suspect I won’t stop doing it any time soon.

It was ideas like these, bouncing around in my head as I stood in front of my barista friend, that made it hard to give a quick and coherent answer to her question about retirement.

««««««•»»»»»»

References

- John W. Budd, biographical sketch,

- Budd, “Whither Work?” blog site

- Chat Room, at the Northwest Film Forum, Seattle

- Budd, The Thought of Work, Cornell University Press, 2011

- Anne Focke, “Unpaid, in Spite of Their Value,” on this site

![]()

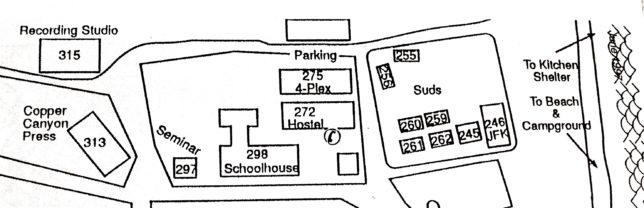

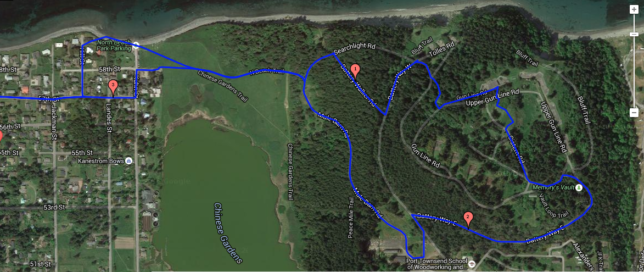

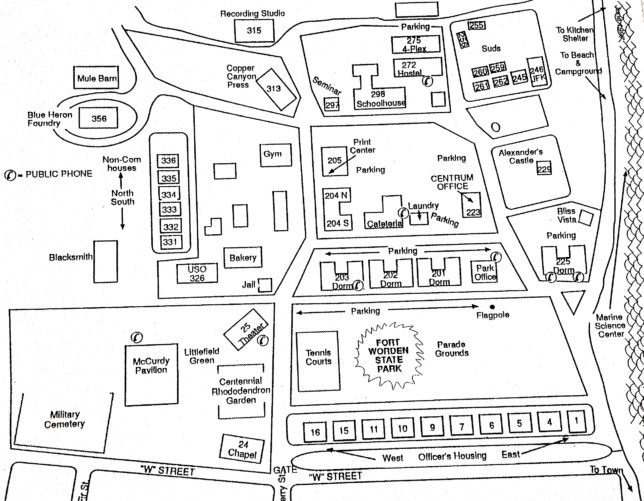

We occupied five of seven buildings that are collectively called, for reasons still mysterious to me, the “Suds” houses. Over the course of the week 21 people participated, including four children of participants. A few of us were able to stay the entire time, others were there for as many days as they could manage. I was given use of the houses as part of a deal I made with Centrum in exchange for services I’d provided in planning and reshaping their artist residency program in the Suds.

We occupied five of seven buildings that are collectively called, for reasons still mysterious to me, the “Suds” houses. Over the course of the week 21 people participated, including four children of participants. A few of us were able to stay the entire time, others were there for as many days as they could manage. I was given use of the houses as part of a deal I made with Centrum in exchange for services I’d provided in planning and reshaping their artist residency program in the Suds.