In mid-January, I traveled about two and a half hours north by bus from Seattle to the ferry landing in Anacortes. Once there, I hurried as quickly as I could, given bulky bags, to the ferry landing and walked on the waiting boat that would take me to Orcas Island where I would soon be house- and dog-sitting for friends. The hour-and-a-half ferry ride took us past many of the San Juan Islands and stopped at two of the more inhabited ones before reaching Orcas. While we sailed, I noticed at least three or four tables-full of my fellow passengers engrossed in jigsaw puzzles.

After briefly wondering why, on such a nice day, the view outside our windows hadn’t captured them as it had me, I wondered how it happened that so many different groups came up with the same idea for passing time. In fact, I learned later that the ferry system itself provides the puzzles, which are often left unfinished as one group disembarks and new passengers pick up where the first group left off. But watching them got me thinking about puzzles.

One of the tasks I’d given myself for my time on Orcas was to take another pass at my stubbornly unresolved desire to find “my piece of the puzzle.” How am I finding my place in our current political, economic, and social circumstances? Am I using my time and specific experience in the best way I can?

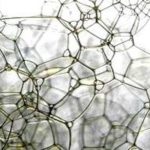

Being surrounded by jigsaw puzzle players made me think about the kind of “puzzle” I actually want to help piece together. From the moment I began asking myself the question, the image I’ve had was of a giant jigsaw puzzle. As I watched the ferry-riding puzzle players I realized my puzzle is not a jigsaw puzzle at all. I’m not trying to help put back together a picture that was once whole – a picture, in fact, that is usually on the box the puzzle came in, propped up in front of the players. The players knew exactly where they were heading.

What faces us in this country right now is not at all like that. We need to be creating a new picture or a new pattern, made of both old and new parts, one that is constantly in motion and changing and that can help us know where we’re heading and, maybe, how we’ll move forward.

![]()

For quite different reasons, the year 2005 was another time filled with reflection on where I’d been, how well I was doing what I was doing, and how I wanted to be working and living in the future. Though I don’t put too much significance on what I call the “big round birthdays,” I turned 60 that year. Both my job as the director of a national nonprofit and also my life and work in Seattle were filled with assessments of my role.

At my job, the board of the nonprofit organization I served as executive director, seemed to go into a fury of evaluation. They asked me to describe my “leadership style,” something I hadn’t thought much about before. I engaged an “executive coach” and created “mini-mentorships” with foundation leaders I admired. I participated in team-building efforts and personality tests with the staff and assisted with a board governance assessment.

At home, in the very same year, “assessment” took a different form as I received several awards and other kinds of recognition for contributions I’d made to the Seattle community over the years. Though only coincidentally coming in the same year, each honor put me in front of a microphone to say a few words – of gratitude, certainly, but also of my perspective on the award, the occasion, or the times – each also a valuable moment of self reflection.

Finally, toward the end of the year, I was commissioned to write an essay that allowed me to reflect on the way I get things done. The invitation came from a writer I admire, Matthew Stadler, who also edited and published (in early 2006) the result, A pragmatic response to real circumstances.* At the time I wondered how I might take advantage of all this reflection and assessment, of feeling “so extensively diagnosed — washed, scrubbed, rinsed, and polished up.” As part of my current search to understand my “piece of the puzzle,” I’ve looked back at that essay to see what I might learn from my 12-year-younger self. Here’s an excerpt:

![]()

From “Risk and drift” in A pragmatic response to real circumstances, 2006

Recently, I’ve imagined that the ages when risk might be easiest would be in our 20s and again in our 60s, before we have a lot to lose and after much work is behind us. In fact, Gene Cohen (M.D. and Ph.D. with a specialty in aging) says that as people move into their 60s, “they often feel free to do something they have never done before. It’s a time when people begin to hear an inner voice thåat says, ‘If not now, when?’ These are powerful feelings of liberation…a counterpoint to adolescence, but with a formed sense of identity.” I have no idea whether this applies to me — or, if it does, maybe “liberation” will simply be a quiet, barely audible release of insecurity and a willingness to own up to my own patterns.

Rebecca Solnit, in Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (2004), recasts this private shift as a part of something much broader:

In important ways, little ripples of inspired activism around the United States parallel aspects of the global justice movement and the Zapatistas. All three share an improvisational, collaborative, creative process that is in profound ways anti-ideological, if ideology means ironclad preconceptions about who’s an ally and how to make a better future. There’s an openheartedness, a hopefulness, and a willingness to change and to trust. Cornel West came up with the idea of the jazz freedom fighter and defined jazz “not so much as a term for a musical art form but for a mode of being in the world, an improvisational mode of protean, fluid and flexible disposition toward reality suspicious of “either/or” viewpoints.

I take heart from that. And Jane Jacobs, twenty years earlier in Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life, articulated a similarly widespread practice that she called “drift,” a kind of work defined not by “practical utility,” but by play, curiosity, and aesthetic investigation. Jacobs described an “aesthetics of drift” and said that successful economic development had to be open-ended and make itself up as it goes along. Her words gave me new ways to understand artists’ work and new ways to imagine their place in the world. Now, I see that much of it also corresponds with patterns that matter in my own life. Here is Jacobs (and the ellipsis is hers):

We might call development an improvisational drift into unprecedented kinds of work that carry unprecedented problems, then drifting into improvised solutions, which carry further unprecedented work carrying unprecedented problems…

![]()

Coda

If ever there were a time that we’ve needed to operate with improvisation, to not rely on old patterns, and to be aware of and participate in the “little ripples of inspired activism,” this is it. We definitely face unprecedented problems and have to be prepared for unprecedented work in the hope that it will lead to unprecedented solutions, knowing all the while that those solutions will also lead to more unprecedented problems. It’s a never-ending process, as implied by the ellipsis that closes the quote from Jacobs.

Clearly, jigsaw puzzles don’t capture the kinds of patterns suggested by words like “ripples,” “improvisation,” or an open-ended process that “makes itself up as it goes along.” Images and metaphors often help make ideas tangible. And if the image isn’t of a jigsaw puzzle piece, what is it?

For ideas, I looked back on images I’ve used in other contexts:

I’m still working on it.

![]()

Notes

* Anne Focke, A pragmatic response to real circumstances, Publication Studio, 2006.

![]()