“I’m going to a baby shower and a death brunch,” Aviva told a neighbor in response to a question about her weekend. It was a Saturday morning in February in my dining room when she reported this with a grin to a tableful of some of my closest friends. We were gathered around a scrumptious meal Edie had made for us that started with a pureed parsnip soup topped with toasted walnuts, followed by a build-your-own Niçoise salad, and finished with homemade macaroons. Aviva, my stepdaughter, was one month from the due date for her second child. The baby shower the next day was for her; the “death brunch” was for me.

A quick caveat may be in order. As far as I know, though of course these things can’t be predicted, I’m not about to die. For now, I appear to be just about as healthy, energetic, and alert as a woman just beyond her 70th birthday can expect to be. To be sure, medical “issues” have accumulated over the years, but I’ve made peace with most of them.

Winter sun, mushroom death suits, and satin sheets

As we talked and laughed and told stories over brunch, the sun periodically broke through, lighting up my living and dining rooms with the special light that can only come from a low late-winter sun. Our talk was alternatively light and serious. We talked about how they’d get into my apartment in case of an emergency. My current home was fairly new to me, and I hadn’t made a very good plan for this yet. We took a close look at my power of attorney for health care, realizing we didn’t understand some of the language and discussed the differences between a health directive and a POLST (Physicians Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment). I have the first but not the second. Retired attorney friend Bob, who drew up the papers, couldn’t be with us, so plans were made to visit him in the next few weeks.

We talked, as we had in the past, about what funeral arrangements I want. This is a task I simply haven’t thought through very well yet. Earlier I had said that I don’t want my body to take up space, so cremation seemed right, and I had researched what Washington State law says about where ashes can be scattered legally. New ideas were also put on the table. I could, for instance, give my body to science. I was already listed as an organ donor on my driver’s license, so this would definitely make sense. A decision would still have to be made, though, about the disposition of the ashes after science was finished with my body.

Of course I could also, Tommer suggested, direct my body to be dressed in a Mushroom Death Suit and participate in artist Jae Rhim Lee’s “Infinity Burial Project.” Not only would the mushrooms in the suit aid in my body’s decomposition and decay (dust to dust, and all that), but the fungi would also neutralize chemicals and toxins that our bodies absorb over a lifetime. The introduction to the artist’s 2011 TED Talk called it a “special burial suit seeded with pollution-gobbling mushrooms;” it would be a very green way to go. The suit, which Lee wore as she talked, looked quite stylish: black with branch-like patterns of embedded spores waiting to be brought to life by a liquid culture after death.

Our topic included not only my eventual death but also emergencies I might not be able to handle alone. So we talked about some of my health and medical conditions, especially ones that had emerged recently. Earlier in the year, for example, I learned that I have Barrett’s esophagus, sort of an extreme version of GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease), where the tissue lining the esophagus begins to resemble the lining of the intestine . . . not what you’d want if you had a choice. For one thing, Barrett’s increases the risk of esophageal cancer. Treatment aimed at preventing or slowing the syndrome’s progression includes instructions to allow 2-3 hours between eating and sleeping, and to raise the head of my bed by 3-4 inches. “Ah,” said Tommer, thinking I’m sure of a sloping bed, “I guess this means you’ll be giving up those fancy satin sheets!”

Endings were its beginning

Our Saturday brunch was the fifth of these gatherings. They got their start six years ago, about seven years after the end of a marriage. I’d finally made time to update my will to omit reference to a husband. When drawing up a will with a spouse it can seem easy to answer questions like who’s first in line to be executor, who has responsibilities in the event of health incapacities, or who knows where your accounts and all your stuff are stored. So without a spouse and with brothers spread far and wide, I turned to Aviva and some special friends who agreed to assume one responsibility or another.

It felt good to complete the revision, but I was also advised that it’s wise to review a will and health directive regularly, adjusting when necessary. “Fat chance,” I said to myself. If it took seven years to revise my will after a divorce, what on earth would get me to review it without an external kick?

Besides the divorce, another ending that led to these gatherings was the death of a close friend who had been an inspiration to me for 35 years. Along with five or six of her other close friends, I had visited Anne during the last eight or nine of her 94 years. She was fiercely independent and would not have been happy to know that “watching out” for her was on my mind when I visited. As these friends of Anne’s came and went in her daily life, we learned of each other. It occurred to me that we should share names, get ways to reach each other, and understand what roles we each played. And we should know how to contact the people who provided her key services – medical, financial, residential. So I put an annotated list together with what I knew and filled it out with help from all the others. I know the list was helpful to me, and I think it also was to others. After Anne died, I began to imagine a similar team and document of my own.

A party!

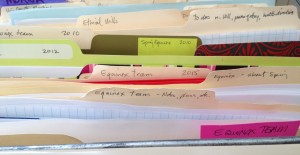

A file folder labeled, “My team,” sat nearly empty in a file cabinet for several years after Anne died until I realized that this team might also answer my need for a regular review of vital documents. The team included seven or eight people: some who had been given responsibilities in my will or my health directive and others who were close friends, next door neighbor, attorney, or bookkeeper.

How could I bring these pieces together? A party, of course!

A few facts provide context. First, it’s much easier to keep commitments to others than it is to keep commitments to myself. Second, I enjoy bringing people together – for conversation, celebration, parties. So I imagined convening my “team” periodically to thank them and celebrate their willingness to be there for me. We’d also review documents, discuss this last phase of life, and have a good time doing it.

An annual event seemed easier to remember than letting several years pass in between. And the date couldn’t be random but had to be tied to something I didn’t control. Putting it off would otherwise be way too easy. A solstice or an equinox would be perfect. I eliminated the solstices: summer comes when everyone’s trying to get away, and winter solstice falls too much in the midst of December holidays. Autumn equinox also comes at a busy time: school begins, work starts up again in earnest after the summer break, and civic and cultural programs kick into gear for a new season. So spring equinox became the date, and I refer to the friends who come together as my “Spring Equinox Team.”

Naw-Ruz, Hilaria, Festival of Isis, Higan no Chu-Nichi, Passover, Easter

After settling on the spring equinox, I discovered many reasons that the choice is even better than I’d imagined. On spring walks I tend to look for old fruit trees that show their age with knobby twists and turns in bark and branches but with blossoms as bright as on any other tree. Spring isn’t just for young trees or young people.

The spring equinox has been celebrated for millennia and by many cultures as a time of death and rebirth, of regeneration. I began to research the mythology and traditions of spring through time. Most mythological, spiritual, and religious traditions mark spring with festivals, celebrations, and high holy days. On the spring equinox Persephone returns to the earth after her six months in the underworld, bringing new life and vegetation. Hilaria, ancient Roman festivals, celebrated the Anatolian mother goddess Cybele on the spring equinox. Especially in the first few years of these get togethers, we talked of what spring means in our own lives. For our meal, we’ve often chosen foods traditional to spring celebrations – eggs, seeds, grains, fish, spring vegetables like asparagus and young greens.

In motion

Gatherings of my Spring Equinox Team take a lightly-structured form that keeps evolving over time. The first year, dinner was the main meal. For the second, we switched and made brunch the centerpiece to adapt to the sleep-nap-meal patterns of my then-one-year old granddaughter, Livia. I’ve not been very strict about hitting the equinox exactly; the date has ranged from early June, in a year when our schedules just didn’t synchronize, to early February this year, in anticipation of a second grandchild. And we missed a year when I moved to a new home at spring equinox time.

Each year, I update two documents: one with contact information for key people (brothers and other family, neighbors, doctors, close friends), and another full of other information that team members might need to know – about my will and health directive, overall health updates, financial files, thoughts about funeral instructions, storage locations, and so on.

What started as a way to make sure I review my will regularly has become much more than that. In fact, though we spent time reviewing my health directive this year, I haven’t looked closely at my will for a few years. More important has been the broad-ranging conversations we have together. We learn something one year that clears up a question from the previous year and takes it off next year’s list. Sources of information to answer specific late-life, end-of-life questions are much more readily available now than when we started, so some topics have fallen away.

We’ve talked about actions to take because I live “solo” and about what it means personally and societally that so many will live 20-30 years longer than people did just 100 years ago. The group helped me test my ideas about moving after 25 years living in one place. Over time, our conversations have become both deeper and lighter. We don’t feel as squeamish talking about what had initially been difficult.

During the first equinox party, Aviva was quite pregnant; about a month later, Livia Rose was born. After that Livia then came to all the equinox parties until this year. Everyone has had a chance to watch her grow, a year at a time. One of my favorite memories is of her standing out on my small garden deck, just bouncing up and down with apparent glee. This year, Aviva was again pregnant, and a few weeks later Henry Ellsworth David was born. With luck, he’ll be joining us next year.

Spring equinox has become a time to celebrate these cycles – baby showers and death brunches, circles of friends, and regeneration!

![]()

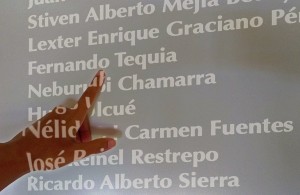

The Lost Defenders of the Environment calls attention to the 991 documented environmental activists who were killed or the victims of enforced disappearances from 2002 to 2014 in thirty-nine countries. It was created by Mika Yamaguchi, Orion Cruz, and Sarah Jornsay-Silverberg for

The Lost Defenders of the Environment calls attention to the 991 documented environmental activists who were killed or the victims of enforced disappearances from 2002 to 2014 in thirty-nine countries. It was created by Mika Yamaguchi, Orion Cruz, and Sarah Jornsay-Silverberg for