What worries you most, and/or excites you most, about the future of work and workers? Put another way: What will be the most consequential changes in the world of work and workers, and what anxieties and possibilities will they produce?

I was invited to respond to this question with a short essay for a column, “The Future of Work and Workers,” in Pacific Standard, a print and online magazine with a U.S. western perspective and a national readership. The Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford asked the same question of business and union leaders, social scientists, technology thinkers, activists, and journalists from around the world. The columns were published every weekday from early August through November, 2015.1 My essay, “Unpaid, in Spite of Their Value,” appeared on November 3, 2015. An updated and slightly revised version of it follows here. — Anne Focke, February 7, 2020

Unpaid, in Spite of Their Value

“I sit as artists have sat for centuries, laboring unpaid. Yet I am sure this is work. I am sure it is productive, and I hope it will be of value.” Marilyn Waring wrote this in the first paragraph of her 1989 book, If Women Counted: A New Feminist Economics. The contributors to this column could have written it now, in 2015.

I’m sure all of the contributors labored over their essays, and I’m certain the columns are of value. They raise questions that matter, offer a wide range of perspectives, identify problems, and suggest directions we might take to find answers, maybe even inspiring us to action. Yet payment was not part of the bargain.

The work of writers and journalists and poets is an essential public good and a fundamental part of civil society. In most cases we work for something more than a financial return. You might say it’s a “calling,” or a strong inner impulse toward a particular course of action, one we likely consider a moral good.

When Marilyn Waring wrote her book, I was an artist and moved primarily in artists’ worlds. Observing us as a group, I wondered why we didn’t seem to fit into the economy, despite hard and persistent work and the value the art gave to so many. The artists around me made a distinction between the “jobs” that paid their bills and the “work” they felt compelled to do. Although some artists find a niche for their work that pays well, the percentage of income that most artists earn from their art work – that is, not from their jobs of teaching, waitressing, data entry, or bus driving – is nominal.

The distinction between jobs and work serves me still. Although I first saw this scenario among artists, many people do work that’s valuable to others but that goes unpaid or is paid poorly. It’s valuable work, but it’s a terrible job. Work that strengthens the common good – caring for the young and the old, teaching and sharing knowledge, making songs and poems, improving the environment, or engaging civically in our democracy – seems to fall low on the pay scale or outside it altogether. And the increasing inequality of our economic system is making this worse. I’m reminded of another column in this series in which Lydia DePillis asks: “Why should a fast-food cook or a home health aide make less than a machine operator anyway?” To which I’d add, is the work somehow inherently less valuable?

Many of us who work in public service or for the common good care about our work. We often actually like working, especially when it matters in the lives of others. The problem is it’s hard to make a living this way.

Can this ever change? Can we who labor for the common good can find common cause? Can we activate a collective will to be part of finding and fighting for solutions that would let us and others dedicate ourselves to work with purpose and meaning, while also making a decent living – with health care, time off, and savings for when we can’t work?

To find common ground we need starting points. The words and music, images and stories of poets and song writers, visual artists and theater workers can inspire us. Our common ground can draw on knowledge gained in many different lines of work to spark ideas and help put words to what we’ve experienced.

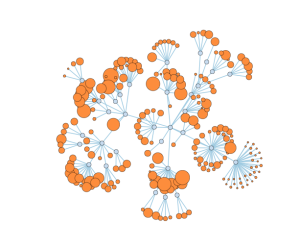

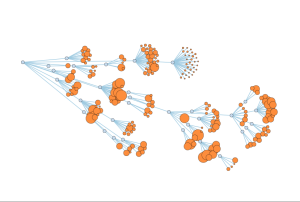

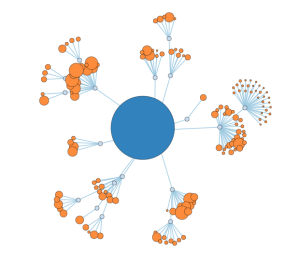

We won’t find common cause in the workplace where workers have found it in the past. The fact is, many of us work in what has been called the “gig economy.” All of us are scattered across distances as independent contractors, freelancers, temporary or part-time workers, and volunteers. How will we find common cause when we don’t have a shared workplace in the conventional sense? Where can we gather and talk, share our anger and frustration as well as our creativity and new ideas? What spaces serve as today’s office water cooler?

As I look around me, I see gatherings already happening in many different kinds of spaces. I hear of more conversations and salons, roundtables and house meetings now than I have in decades. For the most part they don’t emerge from specific workplaces, and they tend to be, like our work, dispersed and unconnected. Some have names, like Soup Salon, Geeks Who Drink, Civic Cocktails, Poetry Potluck, the World Dance Party, Pecha Kucha, Think and Drink, and many more just in my town, Seattle. Others are unnamed and take place in small shared work spaces that we make ourselves in coffee shops, in artists’ shared studios, or in co-working spaces. And yet more take place after work in parking lots and bars and at meetings in living rooms or on weekends in churches and at our kids’ soccer games.

Speaking in Seattle in 2014 about the future of work, Andy Stern – former president of the Service Employees International Union – stressed the importance of aligning our economy with work that’s valuable and needed in society. As one idea, he suggested we find a way to provide a baseline income to people who do this valuable work.2 His closing message was, “We just don’t have a great set of new ideas!” What we need now, he stressed, “is a whole group of people who will come up with a whole new set of ideas for how to do this.”

So where will the ideas come from?

As artists have learned through time, we will just have to do it ourselves, that is, all of us, laboring purposefully and often unpaid. If we come together in many configurations, across different industries and interests, asking questions, arguing, sharing what we know, being inspired to learn more and if we then begin to connect and share with other groups doing the same, we just may find not only the great new ideas but also a revitalized sense of the common good.

Notes

- Pacific Standard has archived many these columns on its website here, and I highly recommend reading others as well.

- In 2016 Andy Stern published a book on this idea titled, Raising the Floor: How a Universal Basic Income Can Renew Our Economy and Rebuild the American Dream.

![]()