“Are aging and the economic slowdown linked?”

A news article forwarded by a friend carried this headline. Without reading the piece, the headline immediately reminded me of a story I’ve tossed around informally for some time. I tend to pull it out in conversation whenever I or someone else in my general age bracket expresses concern about whether or not our money will last as long as our lives will.

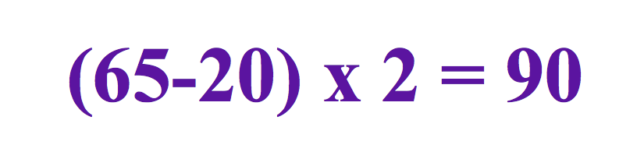

As an equation, it might look like this:

I’ve never expressed it quite this way before, but here’s how I tell the story:

Using round numbers, I say, imagine that I started earning my own living at age 20. I was actually older than that, but it’s close enough and saying I was 20 makes the equation easy to figure out. Then suppose that I decided to stop working for pay at the societally-assumed “retirement age” of 65. I didn’t, but again I’m not quibbling about details. The kicker comes when we add the final assumption, that I might live to be 90. The average life expectancy for a woman my age has been going up and is currently about 86.5 years – again, the number is close enough for the purpose of my storytelling.

The simple arithmetic of the story suggests a conclusion.

Someone living according to my equation would have an earning life of 45 years – just half of a full 90-year lifetime. Hmmm . . . that seems to imply we’d have 45 years to generate 90 years of living expenses, two years’ worth for every year worked. Applied to real life, the equation seems crazy. The equation is all too simple, I know, since it doesn’t account for many things. Obviously, it works well now for a certain segment of the population. For many others, though, the economic life it points to is difficult if not impossible, and on the scale of an entire society, it’s hard to believe that the formula could possibly work.

My equation comes from thinking about the connection between aging and economics in the life of an individual, that is, it’s focused on the “economic slowdown” (or steep decline) in the lives of many older people. The news story I started with, on the other hand, considers the slowdown in the economy as a whole, a slowdown that a new academic study traces to our aging population. Written by Robert J. Samuelson for the Washington Post, the article begins with this sentence:

“An aging United States reduces the economy’s growth – big time.”

The study, out of the Harvard Medical School and the Rand Corp., a think tank, claims that: “The fraction of the United States population age 60 and over will increase by 21% between 2010 and 2020.” Then, Samuelson reports, the study estimates that this aging cuts the economy’s current annual growth by 1.2%, which is approximately the difference between the growth rate from the 1950s to 2007 (about 3% per year) and the rate of growth since 2010 (about 2% annually). This leads Samuelson to conclude, “If other economists confirm the study, we’d probably resolve the ferocious debate about what caused the economic showdown. The aging effect would dwarf other alleged causes…”

Samuelson discusses reasons for why an increasingly older population would reduce economic productivity. It’s partly because there are relatively fewer workers left to support production, but that accounts for only about a third of the slowdown, according to the study. One theory for the rest, Samuelson says, is that older societies may be more cautious with their spending, valuing stability and being more restrained, less experimental and optimistic. On this point, my equation would suggest their “cautious spending” is not necessarily about their sense of adventure but rather about their pocketbooks.

««««««•»»»»»»

You’ll find the Washington Post article, which appeared in the August 21, 2016 issue, here.

![]()

I would suggest that low to zero interest rates are a significant part of the slowdown. I had counted on having a “safe” return of 5-6 percent on a nest egg of about $100,000 or about $6,000 a year to cushion lower earning years. A decade or so ago when interest rates on a money market account were in that range that passive income allowed me to spend far more on discretionary things like travel and home and art. Now with zero income from savings I spend as little as possible and feel an inexorable sense of scarcity looming whenever I look forward in time to when I may not be working at all. I have seen virtually nothing of any depth written about the contraction effect on people over 60 when there is no safe place to put savings and generate income. Many people went through one stock market crash just in time to be reaching their 50’s and ’60’s. How many of those people are willing to put what they have left in the stock market again and risk losing it all at 70? It leaves us cannibalizing our houses, moving to small towns, down-sizing, and taking on room mates.

Great topic. I consider living within our means a challenge to learn new skills to adapt to changes, stay healthy as possible, and work in my community.

Consider tutoring at Seattle World School, at TT Minor, an ESL high school: kids from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

It’s like a free world tour, for nine months.